- Home

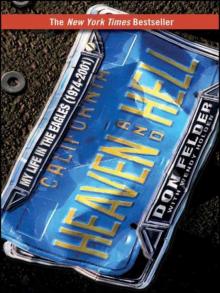

- Don Felder

Heaven and Hell

Heaven and Hell Read online

Table of Contents

Title Page

Copyright Page

Dedication

Acknowledgements

ONE

TWO

THREE

FOUR

FIVE

SIX

SEVEN

EIGHT

NINE

TEN

ELEVEN

TWELVE

THIRTEEN

FOURTEEN

FIFTEEN

SIXTEEN

SEVENTEEN

EIGHTEEN

NINETEEN

TWENTY

INDEX

HEAVEN and HELL

Copyright © 2008 by Don Felder. All rights reserved

Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey

Published simultaneously in Canada

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, fax (978) 646-8600, or on the web at www.copyright.com. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, (201) 748-6011, fax (201) 748-6008, or online at http://www.wiley.com/go/permissions.

Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and the author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created or extended by sales representatives or written sales materials. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for your situation. You should consult with a professional where appropriate. Neither the publisher nor the author shall be liable for any loss of profit or any other commercial damages, including but not limited to special, incidental, consequential, or other damages.

For general information about our other products and services, please contact our Customer Care Department within the United States at (800) 762-2974, outside the United States at (317) 572-3993 or fax (317) 572-4002.

Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books. For more information about Wiley products, visit our web site at www.wiley.com.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Felder, Don.

Heaven and hell : my life in the Eagles (1974-2001)/ Don Felder with Wendy Holden. p. cm.

Includes index.

eISBN : 978-0-470-37018-6

1. Felder, Don. 2. Rock musicians—United States—Biography. 3. Eagles (Musical group) I. Holden, Wendy, 1961- II. Title.

ML420.F3334A3 2008

782.42166092—dc22

[B]

2008009571

To

my mother and father

and

all those who dream of making it

in the music business.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I am indebted to so many people who have helped me over the years, and I fear that my memory might fail me. Frankly, the exact details of some events in the seventies have long since left my consciousness. If I’ve made any mistakes, misquoted or overlooked anyone, then please forgive me.

My thanks go to Susan Felder for sticking it out through all those years; my children, Jesse, Rebecca, Cody, and Leah; Jerry and Marnie Felder; Buster Lipham for allowing me to charge my instruments and for supporting me in the beginning; the members of the Continentals and Flow; Stephen Stills; Bernie Leadon; the Allman Brothers; Creed Taylor; Paul Hillis for teaching me music theory; Fred Walecki; David Geffen; David Blue; Graham Nash; David Crosby; Randy Meisner; Joe Walsh; Timothy B. Schmit; Bill Szymczyk; J.D. Souther; Larry “Scoop” Solters; the late Isa Bohn; and all the road crews during the entire trip. Also to John Belushi, Joel Jacobson, Linda Staab, Skip Miller, Barry Tyerman (for supporting me through it all), Jackson Browne (for standing in for me when my son was born), Cheech and Chong, Jack Pritchett, and Jimmy Pankow and the Bass Patrol, not to mention B.B. King.

Alan Nevins, my literary agent, and Calvin Warzecha (for the best fried oysters I’ve had since my dad passed away), the people at Wiley, and all those I have left out who should be included here.

Wendy Holden for wrapping herself in my life while hers was in such pain.

Kathrin Nicholson for loving me through it all.

Don Felder

Without Alan Nevins this book would never have happened. Without Calvin Warzecha, there would be no Alan Nevins. I am indebted to them both for their professionalism, generous hospitality, and cherished friendship. My husband, Chris, has held my hand through this and so much more; I’d have drowned without him. My friend Robin Richardson has been a source of great comfort and strength, as have my siblings. I shall miss my wonderful parents, Ted and Dorothy Holden, more than words can say.

Don and Kathrin welcomed me into their lives and their home with open arms and made one of the worst years of my life somehow bearable. Thank you.

On a professional front, I am grateful to Ronin Ro for the work he did in the beginning and Marc Eliot for his brave book To the Limit: The Untold Story of the Eagles. Where Don’s memory had failed him, Marc’s text was able to prompt some answers. I also need to thank Marc Shapiro for The Long Run, Ben Fong-Torres for Not Fade Away, Cameron Crowe for the inimitable Almost Famous, John Einarson for Desperados: The Roots of Country Rock, Dave Zimmer for Crosby, Stills & Nash, Anthony Fawcett for California Rock, California Sound, William Knoedelseder for Stiffed: A True Story of MCA, the Music Business, and the Mafia, and John Swenson for Headliners. Also thanks to Randy Meisner for lunch, Karima Ridgley and Mindy Stone for their infinite patience and efficiency, and to Stephen S. Power and all at Wiley for their vision.

Wendy Holden

ONE

We could hear the rumble of the crowd in the dressing room. It sounded like a thunderstorm brewing somewhere far above us. As we emerged one by one from the bowels of the stadium, our lips wet with beer, white powder rings around my nostrils, the rumble grew louder and louder.

The stage was dark as we fumbled across to our respective instruments with well-practiced skill, the cool wind ruffling our hair. The murmur suddenly swelled. Those at the front of the crowd spotted our shadowy figures moving around in the red glow of the amplifiers. They lit candles or cigarette lighters and held them above their heads, hoping for an early glimpse of their rock idols. Others followed in sequence until all we could see was a vast, shimmering sea of light. The anticipation was so heady we could almost taste it.

We stood in the half-light for a few seconds, catching our breath, trying to focus our minds on who we were and how we came to be there. Me, a poor boy from small-town Florida, almost crippled by polio as a child, whose dream was to play like B.B. King, stepping out to the front of the stage. The other four members of the band behind me, from all over the country, in bell-bottom jeans, each of us the living embodiment of the American dream.

There we stood, peering out at the tens of thousands of expectant fans who’d paid top dollar to be here, people who knew each note, every word of our music and who’d come from miles around just to hear us play. The cocaine and the thrill and the adrenaline made my heart pound hard against my ribcage.

Suddenly a spotlight flicked on. Shining straight down

on me, standing alone in a beam of brilliant light, holding a white, double-necked Gibson guitar. The rest of the band silhouetted against a giant reproduction of the distinctive cover photograph of Hotel California, an image of the Beverly Hills Hotel flanked by palm trees in the L.A. sunset. My fingers tingling, I opened with the first distinctive bars of the title track, a song I’d cowritten a few months before, sitting cross-legged on the floor of my beach house with my son playing nearby.

A roar went up. Nobody expected this to be the first number. They thought we’d close with it. The audience exploded. For those first few seconds, there was no sound but that of the crowd—a deafening cacophony of screaming, cheering, bellowing, whistling, and tumultuous applause. Swaying in the spotlight, soaking up the intense, electrically charged atmosphere, I wiped the sweat from my forehead and closed my eyes. As my fingers moved automatically up and down the frets, I allowed myself a small smile. This was it. All that I’d ever dreamed of in the depths of the night—to hear those voices calling from far away—the exhilarating sound of success.

TWO

Gainesville, Florida, probably wasn’t the ideal place to grow up—or at least not the poorer quarter, where we lived. When I was a child, it was an unassuming Deep South community once called Hogtown Creek, where the only means of escape was through dreaming, something I became especially good at.

Its chief attraction was its location, slap bang in the middle of the Sunshine State, three hours from the capital, Tallahassee. It was a ninety-minute drive from Daytona Beach to the east and from the Gulf of Mexico to the west, and about two hours from Orlando, which was nothing until Mr. Disney decided to move there in the seventies. Gainesville’s saving grace was the University of Florida, which for some reason chose to base itself there in 1905, bringing in thousands of people. Hogtown Creek was never the same.

The climate was hot and swampy, the air thick with mosquitoes. In the winter, it was dispiritingly cold and wet. But it was the kind of place where homeowners never had to lock their doors; crime was virtually non-existent. Held in a sort of rose-tinted time warp, it was populated by good, wholesome folks who bred decent kids with strong moral values, helped along by a little healthy Bible-thumping. The Yearling, with Gregory Peck and Jane Wyman, always reminds me of my hometown, with its sugary, apple-pie sweetness. It came as no surprise that Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings, the author of The Yearling and other novels, grew up just outside Gainesville.

My parents, Charles “Nolan” Felder and Doris Brigman, first met on a blind date in 1933, when they were in their twenties. They stepped out for five years—literally walking during their courting because there was no gasoline for Dad’s old Chevrolet during the Depression. Their weekly routine was to stroll downtown to Louie’s Diner, still there today, for a twenty-five-cent hamburger and a strawberry milkshake before heading off to the Lyric Theater to watch one of the new “talking” movies starring the likes of Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers.

My mother’s family were so poor that she and my grandmother actually shared a pair of shoes—Mom borrowing them once a week to wear to Bible school on Sunday. Such poverty often breeds ill health, and Grandma Caroline died of heart failure when Mom was just nine years old, forcing her to drop out of school to care for her father, her older brother, “Buddy,” and her two-year-old sister, Kate.

Dad was of German origin. His ancestors settled in America after riding the trail to Hogtown Creek from North Carolina. They look like something out of an old Western—bearded, with hats and rifles, and with coon dogs lying lazily at their feet. Dad was the eldest of four children abandoned by their mother after she became a chronic epileptic. He was raised by his devout father, who used discipline and the Bible to browbeat his children into submission.

After several years of dating, my father decided, on New Year’s Day, 1938, to take Doris as his wife. They were in Daytona Beach, and to celebrate he bought a bottle of sparkling wine—a rare moment of frivolity. He was twenty-eight years old, and she was five years his junior. With his two best friends, Jim Spell and Sam Dunn, and their girlfriends, they drove to the town of Trenton at ten o’clock that night and woke up the Justice of the Peace. “We wanna get married,” they told the bleary-eyed magistrate. He kindly obliged. They spent their wedding night at the Central Hotel in Gainesville, before going back to their respective homes until they could find a place of their own.

That fall, Dad started work on a building plot he’d acquired at 217 Northwest Nineteenth Lane, Gainesville, right next to the house he grew up in, using his meager savings to pay for the lumber and supplies he needed. The house was built on concrete blocks, with wood framing, designed to circulate cool air underneath and stop snakes and alligators from crawling in. Standing on the edge of a dirt road, surrounded by Florida scrub known as palm meadows, it was flanked at the back by a swampy lake with Spanish moss hanging from the trees. Grandpa Felder helped him with the construction, as did Mom, and so did Jim Spell, who lived next door. My parents moved into a white clapboard shell with a tin roof, identical to Grandpa’s house. They added to it over the years, installing some inside walls to make two bedrooms, a kitchen, and a bathroom. Dad was always so proud of the fact that he’d built his home with his own hands.

For his entire life, he toiled as a mechanic at Koppers, a factory four blocks away at Northwest Twenty-third Avenue, which pressure-treated wood for telephone poles and the railroads. Recently felled trees were brought in by the trainload, and huge machines lifted them onto conveyor belts leading to a giant lathe that peeled off the bark and spat out skinned poles. Another machine loaded them onto rail cars, from which a diesel train backed the poles into a long metal tube. The tube was three hundred feet long and completely enclosed with a giant door. The bolts closed down, and blackened creosote was pumped in under pressure. When the process was finished, the machine depressurized, opened up, and released the sticky black poles onto a rail spur, where another train came in and carted them off to Oklahoma or wherever they were destined for. It was an incredibly slick operation.

Apart from a few years when he was laid off during the Depression, Dad had worked at Koppers since he was twelve years old, long before they had child-labor laws, servicing much of the complicated machinery. Like his father before him, who’d also been a mechanic at the plant, he endured hideous work conditions and unbelievable hours. It was a twenty-four-hour operation, and if there were any problems, night or day, he’d be summoned. I’d hear the telephone ring at two or three in the morning and listen to him stumble from his bed, then come back at dawn for an hour’s sleep before beginning his regular shift. He inhaled creosote and diesel fumes all day long and would arrive home black from head to toe. “Take off them coveralls, Nolan,” my mom would yell at him as he stood out back, before he even set foot in the house. He’d dutifully peel them off and pull open the screen door in his shorts and socks. Taking a long hot shower, he’d try to wash the worst of it away, but the dirt was permanently ingrained under his fingernails and around his cuticles. There was always a lingering smell.

I was born in Alachua County Hospital on September 21, 1947, five years after my brother, Jerry. Dad had missed the fighting because of the importance of his work to the war effort, although I think he might have benefited by escaping from Gainesville for a few years and seeing something of the world. His experience of the Depression had hardened him into a stern workaholic who broke his back for very little pay. Even during brief periods when he was laid off, he’d found employment—laying bricks in the town square outside the courthouse for ten cents a day—and he was always extremely cautious with money. He never owned a credit card, took a mortgage, or bought a car on credit. His frequently repaired ’42 Chevy was our only transport, and he hid cash in his dresser drawer in case the banks ever closed again. Abject poverty can break a man’s trust.

Living as we did on the equivalent of Tobacco Road, I mostly ran barefoot in cutoff jeans and a T-shirt, my faithful cocker spaniel, Sandy, zigzag

ging enthusiastically at my side. With Jerry and my best friend, Leonard Gideon, I’d play in the palm meadows, where we’d make little forts by bending a sapling to the ground with a rope, tying it down, and weaving the loose fronds into a thatch.

Irene Cooter, a matronly sort who lived right behind us, acted as unofficial babysitter to most of the neighborhood kids. Leonard and I would go there for a couple of hours each day after school. In her garden was a huge chinaberry tree, whose roots burled and bubbled up from the ground. “Don’t you go climbing that tree, son,” she’d warn me as I stared longingly into its twisted branches. By the time I was four, the temptation became too much. Needless to say, a branch broke and I fell to the ground with an almighty thud, shattering my left elbow on one of the gnarled roots. Screaming, I ran into the house with the bone sticking through the skin.

The doctors at Alachua County Hospital said I’d end up with very restricted movement and would never be able to do much with my left arm. My mother believed otherwise. As soon as the plaster cast came off, she filled a little pail with sand and made me carry it around morning and night to try to straighten my arm out. I’d cry with the pain and she’d hold my hand and walk around with me, crying too. Thanks to her determination and an agonizing couple of months, I have pretty much full range of motion—very important for a future guitar player.

A year after that accident, I became very ill. I complained to my mother about headaches and feeling tired all the time. It was unusual behavior for any five-year-old, but for a little firecracker like me, it was unheard of. She whisked me off to a doctor, who diagnosed the early symptoms of polio. An epidemic was sweeping the country, leaving thousands of children paralyzed and hundreds dead. I was lucky. They gave me the new Salk vaccine, not yet widely available, and through some miracle, I never developed the full symptoms. But I still spent four interminably long months in the children’s polio ward, frightened and alone. I wondered what I had done to be abandoned by my parents in such a place. Was it because I’d been naughty and climbed that tree? My only salvation was a little radio next to my bed. It had a detachable plastic speaker, and at night I’d slide it under my pillow and lie there, drumming my fingers in time to the music for hours.

Heaven and Hell

Heaven and Hell