- Home

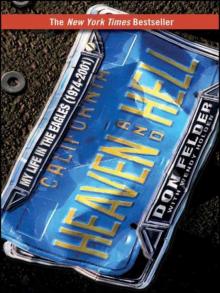

- Don Felder

Heaven and Hell Page 2

Heaven and Hell Read online

Page 2

The sounds of Al Martino and Frankie Laine comforted me and drowned out the wheezing rise and fall of the iron lungs that did the breathing for those less fortunate than me. “Here in my heart,” Al Martino would sing to me as I lay in my bed, staring at a fan slowly whirring on the ceiling, “I’m alone, I’m so lonely.” I like to think it was the soothing music and lilting voices of those fifties crooners, and not the vaccine, that pulled me through.

My mother worked full time, Monday through Saturday, at the first one-hour dry cleaner in Gainesville, which opened at a new shopping center in the middle of town. She’d come home each night with the scent of the solvent and the clothes on her skin. One of the few shouting matches I can ever remember her having with Dad was over her wish to work. “I want my own money, Nolan,” she complained. “I don’t like having to come to you each time I wanna buy something for the boys.” In truth, he’d usually refuse her anyway. My father was indignant. Most wives stayed at home, and he was worried how it would look at the plant. But he gave in to her in the end, as he usually did.

With Mom and Dad both at work, there was hardly ever anyone around the house. Grandpa Brigman, my mother’s father, lived on the far side of town, and we only visited him Sundays after church. Grandpa Felder lived next door, chewing tobacco and spitting great globules of stinking brown saliva into an old coffee can by his feet, but he always took a nap in the afternoons, and I could usually slip away. Without supervision, I’d get into all sorts of trouble—mostly playing music too loud or fighting. I spent a lot of time riding around the neighborhood, filling up the basket of my rickety second-hand bicycle with empty two-cents Coke bottles. If I collected enough empties, I could afford to go to the drug store—MoonPie and RC Cola were the dietary staples of my misspent youth.

I wasn’t the naughtiest pupil at the Sydney Kinnear Elementary School by any means. I was more of a daydreamer, really. I’d spend the hours looking out of the window, thinking about everything from ways to impress Sharon Pringle, a girl I had a crush on, to what scam I could come up with next to raise a few extra cents. School just didn’t interest me. I did the minimum I needed to scrape by and no more.

My parents were forever grabbing me by the ear and ticking me off. My father was determined that his sons should rise above the class we’d been born into and away from the life sentence of menial work he and Mom had been allotted. I think his greatest fear was that I’d end up working at Koppers like him and Grandpa Felder. A dozen times a week, he’d tell me, “Cotton, why can’t you be more like your brother and do something with your life?” (My nickname was “Cotton” because my hair was so white. Later, my nickname became “Doc,” after the famous Bugs Bunny question, “What’s up, Doc?”)

Brother Jerry and I couldn’t have been more different. Bigger physically, diligent, polite, and extremely focused, he seemed to realize early on that the only way to escape the destiny our parents’ limited education had allowed them was to do well academically. A straight-A student who loved to read, he also happened to be a great athlete. A pitcher for the baseball team, he went on to win a scholarship to college and law school. He even married his homecoming sweetheart. In other words, he was an impossible act to follow. I looked up to him in admiration, awe, and envy. Every class I attended, every Little League game I played, the teacher or coach would tell me, “Oh, Felder, we hope you’re half as good as your brother.” Before long, I came to resent the comparison. I soon realized I didn’t have a hope of competing, so I didn’t even try. It was too tall a shadow to walk in, and I’d just slide by instead with D and E grades.

Jerry and I shared a bedroom, with two single beds and a desk between. Most nights he’d sit up late studying, his artist’s lamp shining right into my eyes while I was trying to read Mad magazine, which I could only afford every now and again. One minute, it seemed, we’d been playing together, and then, almost overnight, he was older and more sophisticated, with friends who weren’t remotely interested in his kid brother hanging around. The five-year age gap seemed a chasm between us, and the only time we spent together after that was on vacation or in some sort of competitive sport, at which I’d always lose. He even beat me at Monopoly and chess, having taught me just enough so he could trounce me. Man, I’d be really pissed that he owned all these hotels and houses, and yet he’d make me hold onto one little pink property until he killed me.

I’m sure I was a constant source of exasperation to my father. The memory of his leather strap across my butt and the backs of my legs can still make me wince. It was far worse than the wooden paddle we received at school, and it left angry red weals. I regularly endured his beatings throughout my childhood. It was just part of the deal.

Whenever I think of my mother, on the other hand, I can’t help but smile. It was she who insisted we get Sandy. My father didn’t want pets, but Mom told him firmly, “Every boy needs a dog.” Sandy was my greatest friend, far more so than our cat, Blackie, who seemed to have a litter every other week, usually in the bottom of my closet. Sandy devotedly followed me to school every day and waited patiently outside the classroom until the bell rang. The principal called my parents several times to have him brought home, but if they came to get him, he’d just run straight back, so they finally gave up.

One day, when he was about four years old, I took him to the mom-and-pop drugstore to buy some Pepsi and peanuts. While I was distracted, chatting with the owner about the latest baseball scores, Sandy ducked behind the counter before I could stop him and gobbled up some rat poison. To my horror, he began convulsing almost immediately. Scattering my purchases across the floor, I scooped him up and ran him straight across the street to the vet.

“Please, help my dog,” I said, cradling him as my tears splashed his fur. “He ate some poison and he’s very sick. Don’t let him die.”

Sandy’s eyes were rolling back in his head and he was frothing at the mouth between fits. The vet lifted him from my arms and hurried him into a back room, shutting the door behind him. I sat in that waiting room for over an hour, sobbing piteously, until the vet eventually emerged, somber-faced.

“I’m sorry, son, there was nothing we could do,” he told me as I stood expectantly before him.

I never thought anything could hurt so bad, and I howled all the way home on my bike, ignoring the curious stares of passersby. Fortunately, Mom had received a call at work and was waiting to console me. It was weeks before I was able to go into the drugstore again.

Every Sunday, no matter how tired she was after six straight days working, Mom cooked fried chicken with mashed potatoes and cornbread. I still can’t smell cornbread without thinking of her. For rare treats, Dad would take us to Morrison’s Cafeteria for its Sunday special—ninety-nine cents each for all we could eat. We’d line up with trays piled high with Salisbury steak, chicken, and potatoes, cramming as much as we could into our hungry little mouths until our stomachs were stretched and tight. If they’d have let us, we’d have taken a wheelbarrow.

Regardless of how little money we had, Mom made sure we never starved and were always clean. “Wash your face, hands and feet, behind your ears, and brush your teeth,” Mom would say every night like a mantra. “And don’t forget to say your prayers.” She was a strong Southern Baptist and firmly believed in the Lord. We had to say grace before every meal, even though Dad was often impatient to get on with the important business of eating.

Mom dragged Jerry and me to Sunday school from the time we could walk. Dad never came. “I’ve heard all they have to say,” he’d state flatly, and set about cooking his favorite weekend treat—fried oysters—while we were marched off to the North Central Baptist Church.

Enrolled into Bible-study groups, Jerry and I were being groomed for baptism, which took place in a clear glass tank of water like a giant fishbowl that the preacher and his “victim” would step into. One day, the preacher immersed this big fat lady from the congregation. He placed his handkerchief over her mouth and recited prayers while he

held her under the water. Well, that old dame started kicking and thrashing and trying to get some air, but he wouldn’t let her up. I sat watching, horrified, as she finally burst through the water, gasping.

“Did you see that?” I cried, aghast. “The preacher almost drowned her!” After the service, I walked right across to the Methodist church on the opposite side of the road and signed up there and then. “Methodists,” I told my mother firmly, “only sprinkle.”

The best thing about church for me was the music, not in ours so much, but in the colored churches. Most Sundays, when our service had long finished, I’d walk the mile and a half to one of the “holy roller” churches and sit on the grass outside, swaying softly in time to the powerful sounds and amazing voices that used to pour out of those open windows. Man, those souls knew how to sing a tune.

My parents didn’t have many friends. Neither of them was very outgoing, and both were painfully aware of their shortcomings, having left school at such early ages. The only thing I ever saw my father read was the newspaper, or “mullet wrapper,” as he called it each night when he told me to bring it in for him from the front yard. Even if they had been sociable, which they weren’t, Mom and Dad simply didn’t have the money or the space to entertain. The kitchen was only eight by eight, with a sink and a stove run on bottled gas. You could just about get two people in it if they circled each other. Our tiny living room didn’t allow for parties either.

My mother rarely complained about her lot, but one summer she decided that she simply had to have something—a dining room. Her younger sister Kate had married well, and she and her husband Ursell were the richest people we knew. He’d joined up in the war and stayed on in the military, serving at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Dayton, Ohio. Each time they came to visit, with their kids, Jean and Frank, they’d arrive in the latest Cadillac or Oldsmobile. They lived in a house with a landscaped yard and a garage, and Frank had a motor scooter he’d let me hop a ride on. But most impressive of all, as far as my mother was concerned, they had a separate room for dining.

Each summer vacation, Dad and Jerry and I would spend a week or so working on the house—cleaning or repainting the clapboard, repairing the screens, and making general improvements. There was so much heat and humidity in Florida that the paint constantly cracked and peeled and needed to be scraped off and redone. But this particular year, there were bigger fish to fry: We had to build a dining room. We worked all summer long, every evening and most weekends, sawing boards by hand, hammering, fixing, and painting. When Mom came home from work each night, she carefully scrutinized what we’d done. It was just a box stuck on the back of this old shack, but she’d built it up in her mind to something grander.

Once the dining room was finished, we sat around a table to eat for the first time, instead of from our laps in front of the television. It felt kinda strange having to look at each other over our supper plates. Very rarely was anyone else invited over to enjoy the experience. She even had jalousie windows fitted, louver windows consisting of several horizontal slats of glass, opened and closed by a crank. Lord, she was proud of those windows. So much so, that when Jerry and I accidentally broke them for the first time—fooling around in the yard, I think—she must have taken some small measure of enjoyment from the beating Dad subsequently gave us.

My father was a creature of habit, whose working life revolved around shifts and rosters, everything happening in an endlessly repeating cycle. He made sure his personal life was just as well ordered. For him, there was no stepping outside the box. Every Sunday afternoon, almost without fail, we’d drive somewhere in his old Chevy. My father loved that car. It was an ugly thing, with running boards, but you could stand on the back seat holding onto a rope instead of seat belts. Unattractive as it may have been, it never once broke down. It was such a simple design that Dad could easily repair it. I’d spend a lot of time watching him with his head under the hood, the radio blaring big band music, handing him tools and learning about car maintenance almost by accident.

Undoubtedly, the best times I had with Dad were out in his garage on weekends, fixing something. He’d always secretly wanted to be an electrical repairman, and his workshop was filled with parts of radios, soldering irons, cables, and old stereos. It was his way of relaxing, and he’d never flop down in front of the television with a whiskey like many fathers I knew, chiefly because he couldn’t afford it.

Soon after Sunday lunch, he’d fire up that Chevy and we’d head off to Jacksonville or Palatka or Daytona Beach. For our annual summer vacation, we’d go much farther afield, maybe even to visit Uncle Buck. Dad’s kid brother, whose real name was Jesse, was his jovial opposite. On the rare occasions Dad smiled—and it was usually only when Buck was around—he looked like a different man, his face transformed by lines around his eyes and mouth that were completely unfamiliar to us.

Bored with the seemingly endless journeys Dad took us on, Jerry and I would spend much of the time fighting, nagging, or teasing each other. Conversation was kept to a minimum by the loud music Dad insisted on playing, and we’d stop only for meals or to sleep at nine-dollar motels when he was too tired to drive anymore. The tedium was relieved by the Burma-Shave ads that lined the old two-lane highways. The famous rhyming slogans for shaving cream would be spaced out every five miles, a line at a time, and we’d watch for the next one and wait for the punch line.

Dad smoked Lucky Strike cigarettes, and he’d flick them out of the window when he’d finished, showering us in the back with hot, stinking ash. “Hey, Dad, stop that!” we’d yell indignantly, brushing ourselves off. In my mind’s eye, I can still see his left arm, permanently tanned, hanging out of the window.

Summers in Gainesville were excruciating. Each day dawned with the early promise of heat. By noon, the tin roof was cooking the house. At night, we lay in pools of sweat, barely able to breathe. It was as hot outside as in, and you couldn’t step beyond the screen door for the bugs that would eat you alive.

The winters were cold and damp. The only source of warmth we had in our house was an old kerosene heater, which sat in the open fireplace of the living room. “Doc, go and light the heater,” Mom would call, when it was still dark outside. Reluctantly, I’d jump out of bed, grab some clothes, and rush as fast as I could in the freezing cold. The others would hear the heater fire up and wait ten minutes before daring to peek a toe out of bed. I still bear scars on my butt from where I bent over in front of the heater one morning to pull on my pants and accidentally backed into the metal grate, branding me for life.

My cousin Frank had planted the seed of desire in me for a motor scooter, and I wanted one so bad, but I knew from overhearing Jerry’s battles with Dad on the subject that it would never happen. At fourteen, he could qualify for a motorcycle license and he wanted one even more than I did. Dad thought differently. “You just wait until you’re sixteen, son, and we’re going to put a big piece of metal around your butt. A car’s what you need, not them two-wheel hell on wheels.”

Never one to pay much attention to my dad, I used to sneak around and take rides on the back of other people’s bikes whenever I could, even though I’d almost always end up getting my butt chewed up. I’d come limping home with grazes and bruises all over my legs and arms and try to pretend I’d done it climbing trees.

“Haven’t I warned you about that?” Mom would say, frowning. One day, an older boy with a scooter visited my neighbor across the street. “Please, can I have a ride?” I begged. “Just down to the market?” Under incessant pressure, he finally relented and laughingly rode me downtown and back. On our way home, just a few yards from my house, my neighbor reversed his car out of his long dirt-and-gravel driveway and straight into the side of us. I took the brunt of the impact and was thrown over the top of the car, landing head first on the road before tumbling, unconscious, into a drainage ditch right outside my house. My mother was sitting on the front porch and watched the whole thing in open-mouthed horror.

; I woke up in Alachua County Hospital an hour later, bloodied and bowed, with a concussion but without a single broken bone. A year later, my cousin Frank was killed riding his motorbike. I never sat astride one again.

My mother was very happy with my father but not with her station in life. I think, secretly, she always wanted something better, especially with Aunt Kate doing so well. One particular source of embarrassment to Mom was the family car, which she often complained was old-fashioned and rusty.

Heaven and Hell

Heaven and Hell